30 Birds

30/ Florida Canyon

![]() riving back from our hike up Florida Canyon in far SE Arizona, the conversation turned to Costa Rica. Bob had done the research for his PhD thesis on frugivorous birds there, and the natural question in the minds of both Sheri Williamson and me was "Did you meet Skutch?"

riving back from our hike up Florida Canyon in far SE Arizona, the conversation turned to Costa Rica. Bob had done the research for his PhD thesis on frugivorous birds there, and the natural question in the minds of both Sheri Williamson and me was "Did you meet Skutch?"

Alexander F. Skutch was born in Baltimore in 1904 and was trained as a botanist, obtaining his PhD from Johns Hopkins. The famous (or infamous, take your choice) United Fruit Company hired him to help with the diseases that were threatening its banana crops. Skutch had never been to the tropics before, but like so many other biologists once there he fell in love -- fell in love with the ecosystem.

First in Guatemala, which United Fruit practically owned, then in Panama and Honduras, he eventually purchased a farm in the more pacific Costa Rica and settled there, switching his interests from plants to birds. (For the time before Costa Rica, see especially the chapter "Bird Watching during a Revolution" in his Adventures). "A lifelong vegetarian, Skutch grew corn, yucca and other crops, and, without running water until the 1990s, bathed and drank from the nearest stream. He believed in 'treading lightly on the mother Earth'." So wrote his co-author F. Gary Stiles. There were limits to his reverence for nature: Skutch hated snakes because they ate birds and would kill any snake he encountered. He may have disliked other predators as well. Skutch's observations of birds, many of them on his own farm, gave him the material for more than 40 books, though in fact a few of those books were devoted to his thoughts on morality and religion. He died eight days before his 100th birthday. The online statement that he is "universally regarded as one of the world's greatest ornithologists" is a fair one.

Yes, Bob had met Skutch. They even worked together, in a way. Skutch is most famous for his observations of nesting behavior, and when Bob met him he had just discovered the first nesting occurrence of the Great Jacamar in Costa Rica (possibly the first nesting occurrence of this still-poorly-known bird anyone had seen anywhere). The bird had hollowed out a tunnel in a termite mound. Skutch was very excited about this, and he wanted to keep watch on the nest night and day until the site was abandoned. He could not, however, stay awake 24 hours a day (at least not for very many days), so he asked Bob to watch the nest for him during the time sleep was required. Which Bob did. However, this means that although he knew Skutch, the two in fact had very little contact, just the ritual greeting at the changing of the guard.

We had had a long, steep hike up Florida Canyon, much longer than necessary because we had missed the turnoff we needed in order to find the bird we were pursuing, the Rufous-capped Warbler, and so climbed high up, continually expecting that the small dam we had been directed to would be just around the next turn. The Rufous-capped Warbler is a Mexican and Central American warbler, but on occasion it makes its way up very southern Arizona and very southern Texas. This was one of those occasions, and we were determined not to miss it.

Bob and I had started the day at 4:30 AM at a camp just outside Bisbee. Picking up Sheri at 5, we drove on in the dark up to Tombstone and then took a left onto 82, just before the Border Control station north of the town. By the time we were in Coronado National Forest, on our way to Madera Canyon and Florida Canyon, the sun had risen, though it was still nippy outside now in mid-March. The first birds we saw were very large flocks of Chipping Sparrows. We were looking for Rufous-winged Sparrow as well as the Rufous-capped Warbler, but as so often in my life the sparrow eluded me again. We had the winding road pretty much to ourselves. Sheri said the last time she was here, she found herself in a time warp -- up ahead was a buckboard and a couple in farmer's clothes from 1880. Turned out a movie was being made.On Tuesday evening we drove to Idaho Springs and rented a motel room. We were to rendezvous with three other people later that night, but rather than wait for them we decided to drive up to Mt Evans and check it out. There was a little time before sunset.

We decided first to go beyond the turnoff to Florida Canyon (the Arizona pronunciation is Flor - REE - da) and check out Madera Canyon. I used the Lane guide to birding SE Arizona when I first started and still find useful, and he says: "Madera Canyon is the best-known and most frequently-visited birding spot in Arizona, and with good reason. You can find most of the birds of Southeastern Arizona in a 10-mile distance. If you do not have time to visit any other place, stay in Madera Canyon." I went there a lot, but had not been back in many years.

We stopped by the Santa Rita Lodge and later moved a little further up to road to the funkier Madera Kubo Cabins. The lodge had a flock of tom turkeys displaying to each other, always an amusing sight. The feeders here and at Kubo produced Broad-billed Hummingbird, Painted Redstart, Mexican Jay, Yellow-eyed Junco and others. But we now hurried on to Florida Canyon.

As we neared the trail head there, we encountered a group looking for the Rufous-backed Robin, another rarity in the area. They told us that the Rufous-capped Warbler -- it was beginning to seem as if every bird in Arizona was a Rufous-something -- was just above a small dam along the trail, a fact confirmed by a man and a woman descending the trail that we met soon after starting our climb. They had not looked for the bird today because they'd seen it the day before, but they confirmed the dam. As we headed up, we came to a fork in the path which no one had mentioned; we instinctively chose to keep to our left. Huffing and puffing, and in my case peeling off pullovers, we came to a metal gate. To our right, across a dry gully and behind a barbed wire fence was a forest research station which all the birding sites are careful to say is off limits. We opened the gate and continued the steep ascent.

A half hour later, after many huffs and puffs, Sheri was the first to say that we were now in the wrong habitat -- too dry, no water anywhere, just shrubs and ocotillo. The view was great, but that was not what we had come for. I went ahead in the vain hope that a dam might lie further up. Later Bob went even further ahead in the even vainer hope for the same thing. But we all eventually decided that perhaps we had taken the wrong path when, down below the metal gate, we had gone right rather than left.

We were alone on the trail. The whole couple of hours we were up on the canyon trail, the only people we saw were those two descending birders we'd met at the outset and, later, a non-birding photographer in a big black cowboy hat. It was quiet. No fracking going on here. I was reminded of a study some people had done of the effect on birds -- and on the dispersal of seeds and pollen -- of natural gas extraction, day and night, in Rattlesnake Canyon in NW New Mexico. The noise scared away the jays, but Black-chinned Hummingbirds prospered, probably because of the reduced population of jays.

Bob and Sheri had a good time identifying a number of the flowering plants on the way back down the trail, starting with the humble Desert Dandelion. "To see a world in a grain of sand/And a heaven in a wild flower . . ." but we were in pursuit of a bird. Sheri saw a lifelist butterfly, a small white one, maybe the Florida White. I didn't get the name; I was pressing on. Sheri, a transplanted Texan (Fort Worth), is the author of the Petersen field guide to the hummingbirds of North America. She is of course a terrific birder, her ability to hear and recognize birds even in the far distance is especially notable, but she is also impressive in that she knows the rest of the biodiversity in Arizona as well.

The range map shows a bird of the Mexican mountains broadening out when it reaches the center of the country, then proceeding along the Pacific coast all the way to the Panama Canal. Remarkably there is a separate second population in Colombia, a broad stripe on the Caribbean coast narrowing substantially as it proceeds down the mountains almost to the border with Ecuador. Apparently, some authorities classify this as the Chestnut-capped Warbler.

What the internet tells us about the bird's life history:

Breeding: courtship song, "a rapid, accelerating series of chipping notes (chit-chit-chit-chitchitchit), somewhat reminiscent of the rufous-crowned sparrow, while the call note is a hard chik or tsik, often repeated."

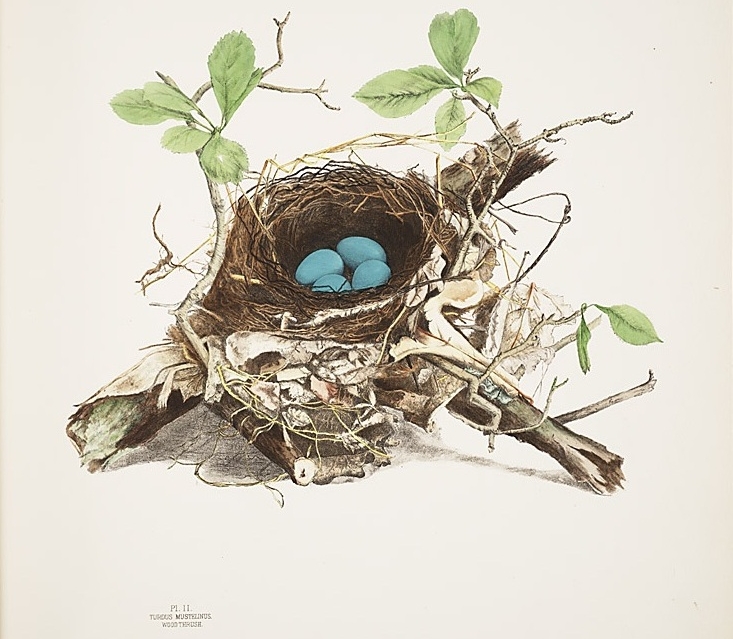

Nest: "oven-shaped, with a side entrance, of various vegetable materials, thickly lined with shredded bast fibers, well hidden amid litter . . . beside or between rocks or fallen logs, sometimes in a niche in a high bank." 2 - 3 eggs.

Feeding: "insects and spiders, foraging through dense brush and scanning close to the ground for movement . . . not generally known to flycatch from perches."

When we returned to the metal gate, Sheri looked over to the research station and became convinced that there was actually a path somewhere across the gully that would take us up behind the station without intruding. She found it, and we followed. Not long after, we discovered the dam, a small affair but one with water and green vegetation behind it. The couple coming down the path had mentioned a large sycamore tree. We began looking for Platanus wrightii.

Bob pointed out a sycamore that wasn't that large, but which seemed like it might be the one. There was a small creek alongside us coming down to the dam, between us and the sycamore. The creek was choked with bright green willows and other vegetation. We scanned all this, but could find no warbler.

We decided to spread out along the creek, though we did not go far, and wait to see what appeared. There was a small cliff face behind our backs. We could lean back against that. I was nearest the dam. Bob was about fifteen or twenty yards further up and Sheri about the same distance yet again. It didn't take long. Bob put his glasses up and announced the Rufous-capped Warbler. We moved over to his position and all got good looks at the bird as it hopped around in the willows. We saw a second one, too.

What a beauty! The word "rufous" has never done more elegant work. The cap or pileum is the epitome of rufous, but so is the area directly behind the eye, the auricular. The small patch directly below the eye is gray, and a black eye-line, seemingly drawn with a piece of charcoal, connects the black bill and the black eye. Above the eye and separating pileum and auricular is a most attractive bright white eyebrow or supercilium, extending all the way from the base of the bill to the beginning of the back All this highlighted by a bright yellow throat and chest. The underside continues yellow in birds in the southern part of its range, which extends into northern South America, and these birds are claimed by some to constitute a separate species, the Chestnut-capped Warbler. I prefer the gray underside of our bird because it emphasizes the yellow which in turn heightens the colors of the face. The back and tail are a drab light brown, which further emphasizes the front of the bird.

The charming character of a warbler, the North American Wood Warbler, was on display also. Small, active, amiable, as if it wanted to be seen but not to be too obvious about it. The first birds I saw when I started bird watching were warblers, the Myrtle Warbler (now the Yellow-rumped), and the Black-and-White, creeping up a tree trunk. They've had me in their grip ever since. Adding this new one made for, as my daughter would say, an excellent adventure.

Bob and I had been out together many times in search of a very different bird, the Montezuma Quail (known locally as the Mearns). Bob wintered for quite a few years in Double Adobe, just outside Bisbee, AZ. Each year I would drive over from Oracle, where I was staying with other friends; Dr Jenkins and I would then set off on our quail quest. Each year, in preparation for this, Bob would speak with one or more of the birders who live in the area about whether they'd seen the Montezuma recently and, if so, where. This always turned out to be an area in Coronado National Forest on the Mexican border. We were told of quail families crossing the road, quail sitting on top of shrubs, quail underfoot. Each year we would drive in his 4x4 over high mountainous hairpins to arrive at the top of the part of the forest that is a desertscrub environment running down to and along the border. Each year we would traipse through this for hours, usually with the aid of his hunting dog. We were alone in this extensive wilderness, save for the occasional Border Patrol vehicle. The fence along the border was a simple chest-high wooden post-and-rail fence, like those you see along the road marking the edge of a ranch. Each year we would be disappointed. We could, however, each year, console ourselves by dining on the best Chicago Italian Beef Sandwich west of the Mississippi at a small place outside Bisbee. Actually, on our last visit we did scare up a female Mearns, possibly a juvenile male. We were both convinced, but we did not in fact see enough of the identifying features to count it.

Like hummingbirds, wood warblers are confined to the New World. They don't, of course, warble. It's just that the name was used for this family new to European settlers because some of them (the warblers, not the settlers) bear a resemblance to the birds who do warble in the Old World, particularly to the -- just to make matters more confusing, the Wood Warbler, or perhaps I should say The Wood Warbler. Our warblers constitute the Parulidae (with the recent exception of the wonderful Olive Warbler, now placed in its own family, the Peucedramidae). Those in the Old World constitute the Sylvidae, or rather used to constitute the Sylvidae before all hell broke loose in taxonomy and they ended up in ten families, not to mention the species incertae sedis. We have about 109 species over here, about 56 of which are found north of Mexico. Most species largely eat insects, but some add berries or even sap. There are many remarkable individual species: Kirtland's Warbler, for example, has the most restricted breeding range of any continental North American bird; the Olive Warbler's new family, to take another example, is the only family endemic to the area north of the Panama Canal that nests mainly in trees, shrubs and rivers, but some also in tree holes or hanging moss or lichen. Not too many people realize that some warblers engage in an activity more widely associated with the Killdeer: feigning injury in order to draw intruders away from the nest; these displays can be quite elaborate.

I have to say that one of the most remarkable things about seeing the Rufous-capped was how genuinely delighted each of the three of us was. We were like kids seeing something new. We each have seen a lot of species in a lot of places, but that in no way weighed us down. There were smiles all around as we started back, beaming smiles, if I do say.

We came down the mountain to the small parking area at the head of the trail where we had left the truck. Sheri and I opened the doors and grabbed bottles of water and headed for the shade to drink them. Bob crossed the road to look over the barbed wire fence into the trees and shrubs there. A bird flew up into a sapling, and he thought it was the Rufous-backed Robin. He looked away to call us, and the bird vanished. No amount of subsequent searching by the three of us could produce the bird again.

Costa Rica came up again on the way back to Bisbee. Bob told us about a flock of birds he'd seen there while his mother was visiting which numbered perhaps two thousand individuals. Later, when I asked him to remind me how many species he had said were in the flock, he replied:

I estimated 200 species. It couldn't have been a single flock, but it looked that way. My mother and I just stood there and watched it pass for two hours and there was no moment during all that time that we weren't busy trying to guess at the identities of a couple dozen birds simultaneously. As I've told you, it was tough identifying CR birds in those days -- no field guides. All I had was NA guides, which were fine for the migrants, a couple Mexican guides, Meyer de Shauensee's Venezuelan guide (with only a handful of illustrations), and Paul Slud's un-illustrated annotated check list for Costa Rica. Also, I started drawing my own guide in colored pencil, but I didn't get very far -- just most of the tanagers and a few others. I could maybe identify maybe half of what I saw to species or genus, the rest to family, and it was all going on so fast that mostly all I could do was stand there and jot down notes about the third species of piculet, the sixth Furnariid, that great big Dendrocolaptid, the fourth cotinga, the eighth warbler, etc. I probably listed a hundred species to myself or roughly identified them for my mother and I guessed I'd seen as many more that I didn't have time to do more than recognize as different or just seen flitting through the foliage. We were on a path along a steep ridgeline, by the way, with the canopy from the lower level forest right at eye level, so much of this was transpiring in the canopy. I glimpsed a score or more species I never saw before or after. What I marvelous place. On another day, when something caused me to clamber down the side hill, one thing I discovered was that what I had thought was a mixed grove of trees was a single huge central tree with a dozen or more lianas hanging down, some of which were more than a foot in diameter. That's the sort of place it was.

But then:

I think I told you that when I returned to Alto de Guayacan many years later I was stunned to find that all of this had been absolutely cleared, from the Rio Paquari to the Rio Reventazon -- one of the saddest moments in my life.

Chapters are sometimes supplemented by notes. Click Random Footnotes to see.

Table of Contents

Home page ->For a listing of chapters that includes each bird's name, click on Random Footnotes.

All is journey, and in this case, 30 journeys. We can make these particular journeys riding webbook or ebook. The complete ebook, sans ads of course, is available now for

purchase: Click here.

The introductory web posting of the first two chapters is in full. Click Additional for other postings.

Birds treated, but not featured (see Photo Credits):