30 Birds

2/ Above and Above

![]() e flew from Dulles to Denver on a Saturday morning in October. Dr Chipley and I immediately rented a car and drove west of the city to Guanella Pass, a pass so high in the mountains (11,665 feet) that it is above timberline. The rocky tundra you find when you get up there is suitable habitat for the ptarmigan, just as if you had driven a thousand miles to the north. Hence, Guanella Pass is "the best spot in the United States to see the White-tailed Ptarmigan in its winter plumage."

e flew from Dulles to Denver on a Saturday morning in October. Dr Chipley and I immediately rented a car and drove west of the city to Guanella Pass, a pass so high in the mountains (11,665 feet) that it is above timberline. The rocky tundra you find when you get up there is suitable habitat for the ptarmigan, just as if you had driven a thousand miles to the north. Hence, Guanella Pass is "the best spot in the United States to see the White-tailed Ptarmigan in its winter plumage."

Try to imagine getting out of your car at that altitude, climbing a rocky slope and clambering about searching for a white bird about the size of a chicken -- all this right after a long plane ride. The wind is blowing, and it is quite cold, even though the sun is shining. Distorted, stunted trees (the sort of thing ecologists call "krummholz") are on hillsides here and there, but mainly grasses and low, leafless willow bushes on the buds of which the ptarmigan is able somehow to subsist during the winter -- even to gain weight. (Their diet gives their flesh a bitter taste, apparently). You do not have to clamber about very much to be out of breath. Jet lag does not aid the process of acclimatization. Nor does not finding the bird after several hours of searching. I had a headache.

We packed it in and drove back to Denver and then north to Ft Collins, for on Sunday we were going to explore the Pawnee National Grassland, a vast short-grass prairie in the northeast corner of the state and so very different in every way from Guanella Pass that it difficult to believe they are in the same state.

On Monday, at our conference in Estes Park, Dr Chipley ran into John Humke and told him that we had been looking for the ptarmigan. John said that a few days ago he had driven out to the summit of Mt Evans before dawn because he wanted to see the sun rise out in the wilderness there. Climbing the last ridge to the summit (the road is gated and impassable before the actual summit, so you have to walk), he noticed these white birds flying about in the first light.

Naturally, we set our sights on Mt Evans. It, too, is west of Denver, but not so far as Guanella Pass. The nearest place to stay is Idaho Springs. We had a little time before our plane left on Wednesday morning.

On Tuesday evening we drove to Idaho Springs and rented a motel room. We were to rendezvous with three other people later that night, but rather than wait for them we decided to drive up to Mt Evans and check it out. There was a little time before sunset.

The drive was only about 35 minutes. The sun had set by the time we arrived, but there was still light as we drove past icy Summit Lake (12,830') and pulled up to the gate. There was another car there.

When we got out, a bitter wind went through my hooded, heavily-thinsulated parka and chilled my bones. In front of us stretched a warped blacktop road that goes on for a mile or so and then loops around to the right and approaches the summit from the rear. On our right was the summit itself, about a thousand feet above us -- the end of a long ridge (rather than a point) that extended back of us and around Summit Lake. To our left, tundra and rocks, sloping off, with the streets of Denver lit up in the extreme distance.

We put our heads down into the wind. Dr Chipley kept his eye on the tundra above the road and to the right; I kept my eye on the road and on the area below. There were patches of ice here and there, but almost no snow. We pressed on into the wind. Dr Chipley then scrambled up some boulders, and I went on ahead. I saw a dark, furry mammal about the size of a marmot scurry across the road in the distance and disappear behind a boulder. (Marmots according to the book, though, hibernate as early as August). When I got up there it was nowhere to be found and was obviously safe from me in a burrow.

Dr Chipley reappeared on the road as we encountered the man from the other car returning. We asked him if he had seen any birds. Yes, he thought he had, up above where we were standing. What color were they? "The same color as the rocks," which made us discount this evidence. The light was fading, and it was bitterly cold. So we did not go much further, and then we, too, returned to our car.

Larry Master, Margaret Ormes, and Kathy Schneider met us in Idaho Springs, and we all had dinner together. We departed the next morning at 5:30; we were in the lead. There was not a glimmer of light in the sky. On the way up, we passed a porcupine lumbering slowly across the road. Further on, a deer mouse crossed in front of our car and then paused long enough on the dividing line that we able to pull up to it and see its large ears fairly well in the headlights of Larry's car.

We pulled up to the gate and waited for some light. It came on ever so faintly, and well before there was any thought of sunrise. When there was enough to add some color to the ridge on our right, we got out and braved the wind. I had put on a pair of Levis under my khaki pants this time, and I had on two sweaters underneath the parka. I forgot to mention that I had a cold.

The five of us started up the road cautiously, fighting our pessimism that we weren't really going to see anything. Maybe it had not been such a good idea to leave a warm bed at such an ungodly hour. Then suddenly Larry shouted, "there they are," pointing up. I saw three white projectiles shooting right to left at the very top of the mountain, and then another. We started climbing the ridge, making for the very top of the mountain. We had not gone far before we were out of breath and had to pause. We started again when we had caught our breath. When we had made it about half way up we could see the birds on the ground ahead of us. We could get good views through our binoculars as they walked gallinaceously about in the tundra grasses. We could see about a dozen of them at first. The molt was almost completely white. Only on the back of the head and neck and along the spine were there a few of the tundra-color feathers that protect them from raptors in the summer.

The birds were not shy and did not fly away as we approached even closer, though they did keep some distance between us. We could see about a half-dozen more of them. On closer inspection I could see the famous feathered feet (the nostrils also are feathered, apparently). The feathering keeps the feet from freezing. The white plumage was quite beautiful. I could see it ripple in the wind. I had the impression of a woman in an ermine coat.

When I turned to leave, the back of my parka presented a sail to the wind and a sudden gust knocked me off my feet and down the hill. I was completely out of control for about 20 feet. The soles of my tennis shoes were slippery and were of no help until they finally managed to gain some purchase on one of the boulders embedded in the tundra.

On the drive down the mountain we came upon a small herd of Bighorn Sheep, ewes or young males because their horns did not have the full curl of the ram. They were quite tame. In fact, some of them were looking for handouts and came right up to the open window.

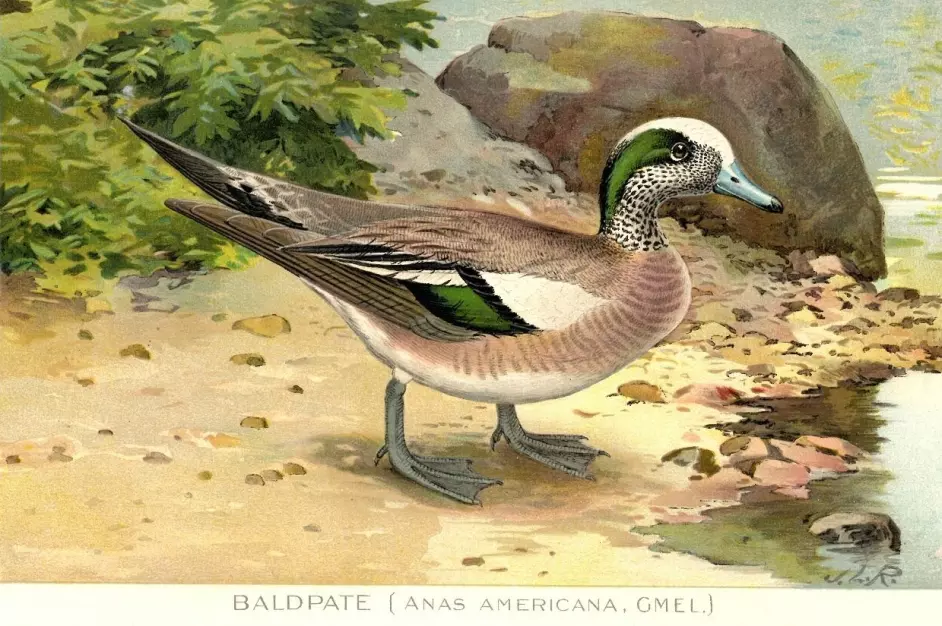

The White-tailed's ability to survive, even to prosper, in the extreme, cold environment where we first encountered it is certainly a remarkable characteristic, but there are others, one in particular. As to the cold, the distribution of the bird is mainly in Alaska, the Yukon, and the mountains of British Columbia -- the birds in Colorado (some can even be found in far northern New Mexico) are a noticeably disjunction population. What do they eat that enables them to survive in winter in these punishing environs?

They actually eat pine needles, and even more remarkably they eat twigs -- from willow and alder trees, buds and seeds, too, if they can find any. Accounts of the ptarmigan's diet typically just list these food items and leave out the AMAZING. One study found that these foods (I'm inclined to put the word in quotes, but the fact is these really are foods) require special bacteria in the bird's cecum -- a pouch at the beginning of the large intestine -- to extract "essential nutrients" during digestion. I wonder whether these bacteria are unique to the White-tailed Ptarmigan, or to ptarmigan in general, and whether they are also found in some other bird species.

Even more remarkable in some ways is something that occurs in the warmth of the summer months -- communication between the mother hen and her chicks, in a way that has been described as "social learning" or even "cultural transmission."

Our findings indicate that the white-tailed ptarmigan hen's food call is a form of cultural transmission in which information regarding available food is disseminated from hens to chicks. Hens chose foraging patches where certain plant species were abundant and called their chicks to these foods, which dominated their diet. Chick consumption mirrored the calling rates of hens and as a result chicks ate high-protein foods, which are critical for chick growth and development. The results suggest that white-tailed ptarmigan hens' food calls may function to enhance survival of juvenile ptarmigan.

This is from a two-year study done by Traci Allen and Jennifer A. Clarke in Rocky Mountain National Park and published in 2005 in the journal Animal Behavior. It must have been enchanting to watch the hen saying, in effect, "Hey, come on over here, away from those insects you've been munching on, and dig into these delicious willow catkins and the flowers of mountain avens and chickweed. There are also yummy lichens -- even berries; I know you're going to love those." That's this layman's interpretation, anyway.

A popular bird, the White-tailed Ptarmigan has been introduced into a number of areas. One not so well known is the Wallowa Mountains in the northeast corner of Oregon, mountains which are known as the "Alps of Oregon." There's even a Matterhorn. Another is the Uinta Mountains of Utah, a subrange of the Rockies, noted for extending east to west, the highest range to do so in the contiguous US. I believe the most extensive introduction has been to the Sierra Nevada in California, at Eagle Peak and Twin Lakes, Mono county, above Mono Lake.

In the middle of the July after our October trip, a group of my friends and I -- a different group from the one on Mount Evans -- drove up Trail Ridge Road in Rocky Mountain National Park to one of the highest points. The weather was warm and beautiful. We stopped our car, crossed the road in the bright morning sun, and climbed up to the snow patches visible above us. We were looking for Brown-capped Rosy Finches.

We were there out of a sense of completeness. Once North America had three species of Rosy Finch, but they have lately all been lumped into one. The three that existed before are now considered but separate forms of the one revised Rosy Finch. We had all seen the other two races, but we wanted to see the third. Some of us, me included, had only seen Rosy Finches at feeders; here was a chance also to round out one's experience of this species by observing it in some characteristic behavior: hopping around on the melting snow catching tiny insects as they emerge from their winter sarcophagus.

We saw the Rosy Finches, drab brown females -- or possibly males far drabber than the field guides show. On the way down, we examined the alpine wildflowers, tiny but stunningly colorful: the deep-blue Forget-Me-Nots, the buttercups, the red paintbrushes, the towering 2" tall Old-Man-of-the-Mountains, a sort of miniature sunflower with the same sun-facing propensities.

One of us nearly stepped on a ptarmigan. The bird moved about two feet away from its nest, and waited calmly while the rest of us came to look at the three tan, speckled eggs.

Here was a remarkably different bird from the ones we'd seen not so many months ago. The brown mottling blended perfectly with the matted alpine mosses and the lichen covered rocks. Only the underside and the feathered legs (each with a man-made band) and feet were white. The bird was plump and soft and just as impressive in mottle as it had been in white. It was not afraid of us.

![]()

Chapters are sometimes supplemented by notes. Click Random Footnotes to see.

![]()

Table of Contents

Home page ->For a listing of chapters that includes each bird's name, click on Random Footnotes.

All is journey, and in this case, 30 journeys. We can make these particular journeys riding webbook or ebook. The complete ebook, sans ads of course, is available now for

purchase: Click here.

The introductory web posting of the first two chapters is in full. Click Additional for other postings.

Birds treated, but not featured (see Photo Credits):