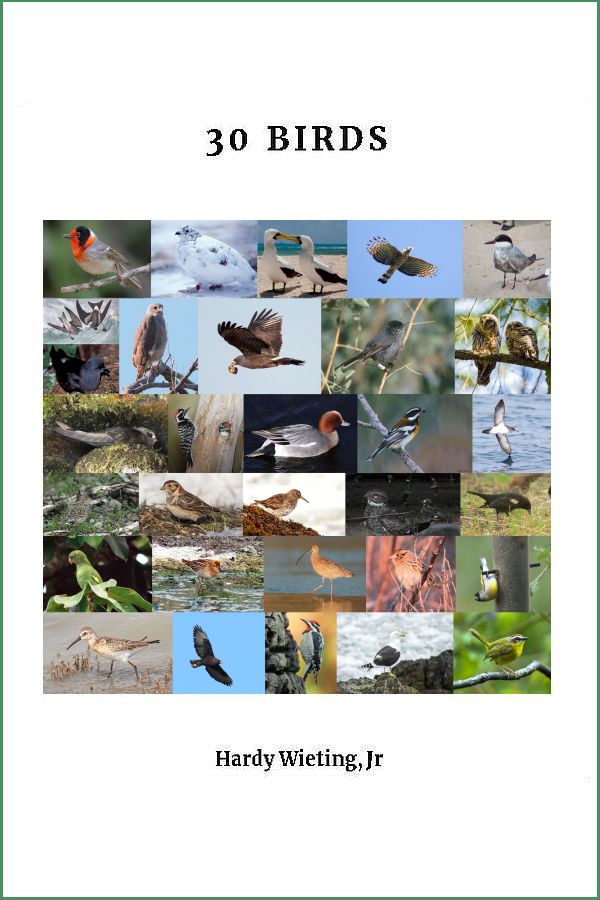

30 Birds

13/ Penelope

![]() ne December day, I was in Sacramento. I was in possession of a bird-finding

supplement written by Joel Hornstein from Birding magazine that begins, "An excellent opportunity to see Eurasian Wigeon is afforded the winter visitor to the Sacramento National Wildlife

Refuge in Willows, California." I was a winter visitor. I had a friend to help me. And I had a few hours before dark.

ne December day, I was in Sacramento. I was in possession of a bird-finding

supplement written by Joel Hornstein from Birding magazine that begins, "An excellent opportunity to see Eurasian Wigeon is afforded the winter visitor to the Sacramento National Wildlife

Refuge in Willows, California." I was a winter visitor. I had a friend to help me. And I had a few hours before dark.

We drove north on I-5. I was struck during this dull drive, as I always am, by how much certain parts of the broad plains of the central part of California look like the broad plains of the state in which I grew up, Illinois. Blindfold farmers from the Land of Lincoln, drop them down in this habitat (at the right time of the year), and they would be somewhat hard-pressed to determine that they had left home -- save for the mountains in the far, far distance here. We exited on CA 99 and continued north. The sky was gray, and it was cold.

Actually, we weren't heading for the refuge. We were heading for Gray Lodge Waterfowl Management Area, a state facility. The bird-finding supplement mentions this area also ("another excellent place"), and it is a little closer to Sacramento. It is also an interesting place, typical of many wildlife management areas across the country. Like most such areas, it only looks wild: in fact, it has been altered by humankind for centuries, in this particular case possibly as far back as when the Maidu and Wintun Indians lived in the area. The Gold Rush resulted in great change. The area was drained and diked in order to create farmland. The farming on these few thousand acres must not have been that good, however, for in the early part of this century, neighboring farmers restored some of the wetlands in order to improve the duck hunting. They formed a club and built a gray lodge. In 1931, the state bought 2,500 acres and began professional management of the area. It was also an effort to attract waterfowl away from the neighboring farms and thus to reduce crop depredation.

After the initial purchase, the state continued to buy. Today the area is about 13 square miles, or 8,400 acres. (Cal Fish & Game manages over 600,000 acres altogether, when last I checked).

We turned left off of 99 at the sign in Live Oak. About ten minutes later we found the entrance to the area. As we drove up the access road, we could see hunters chatting with each other or playing with their dogs after a day out in the cold. Our rental compact elicited a few glances, here among the trucks and the jeeps, but we drove serenely on to the start of the wildlife observation tour route.

At stop 16, we began to see ducks in the ponds on either side of the road. These were wigeon. I had, unfortunately, not prepared very well for birding on this trip, believing when I had arranged the trip that there would be no time to pursue any new birds. I had my binoculars, but I had left my National Geographic field guide at home. I did have my very old Golden Guide, but only because I have never bothered to take it out of the front pocket of my knapsack.

Alas, the illustration in the GG (of the "European Widgeon") is not a good one. The Eurasian male is shown with its head facing us, looking over its shoulder. With the bird's head in this posture, a posture which emphasizes the forehead and cap, little of the side of the head can be seen -- but the area around the eye is dark, suggesting a face patch similar to the American's should the bird turn its head to the side. The cheek is shown as reddish brown, but the impression is given that the main difference from the American is the color of the forehead and cap -- creamy on the Eurasian and white on the American. (The American was originally known as the "baldpate").

We searched, my friend Keith Carr and I, for birds with a creamy forehead and crown. We found some, more than I had expected. Or thought we had, in the diminishing light. I had expected -- even here on the West Coast in winter -- the Eurasian Wigeon to be a rare companion of the American, rather as the Barrow's Goldeneye is to the Common. Indeed, the Golden Guide says the bird is a regular fall visitor, "though never in large numbers." But here creamy crowns were not infrequent. Was this just some effect of the dying sun, adding color to what would otherwise be white?

The day was darkening fast. It began to rain. We stopped at a few of the other ponds, but we saw nothing new. We departed.

These were not, of course, Eurasian Wigeon we had been looking at.

Back home it was possible to look into identification in more detail. The illustration of the Eurasian mature male in the National Geographic guide has the bird in the same over-the-shoulder posture as in the Golden Guide. The portrait is substantially larger, however, despite the fact that the it is fitted on to a page illustrating more plumages. This is partly because the dimensions of the page are larger, but mainly because the left side of the page is not given over to birds in flight displaying speculae. The result is a much better aid to identification. There is no hint of a dark face patch. The forehead and crown are a lighter color, so that the contrast with the forehead and crown of the American is not so sharp and more emphasis is placed on the reddish-brown of the head. Sibley shows everything in profile, with a "buffy forehead" pointed out for the adult breeding male, "Oct-Jun." This is lacking in the adult nonbreeding male, "Jul-Sep." Sibley also illustrates two hybrids between the American and the Eurasian, both of which have dark around the eye and buffy foreheads of varying degrees.

But in the end, none of this made any difference.

Ten months later, Wednesday, the 5th of October, I was driving back to DC after attending a meeting at that Long Island gem, The Nature Conservancy's Mashomack Preserve.

Edged in white by 11 miles of coastline, Mashomack Preserve on Shelter Island is considered one of the richest habitats in the Northeast. Just 90 miles from New York City, the preserve covers a third of the island with 2,039 acres of interlacing tidal creeks, mature oak woodlands, fields, and freshwater marshes and is often referred to as the "Jewel of the Peconic."

I decided to return by a more interesting route than I-95: via the Garden State Parkway, which is much closer to the Jersey shore, then the ferry from Cape May to Lewes, DE, then to the Chesapeake Bay and across it on the Bay Bridge, past Annapolis, and on into DC. I particularly like the ferries, which are made by the same company that makes the ferries that ply the San Juan Islands, three thousand miles further west.

When I arrived in Cape May, I found that I had some time before the next ferry, so I drove over to Cape May Point State Park and Natural Area. The park is a small green patch painted along the very southern end of the Cape May peninsula and the tourist town of Cape May. In addition to its historic lighthouse, once lighting the way for ships in Delaware Bay, the park has ponds and trails and beaches. But it's all about the Fall Migration. The peninsula is like a finger pointing the birds the way south, and huge numbers take advantage of this, as do birders. There's a Bird Observation Deck, just to make things easy, and this is used principally for hawk watching. Trails are for songbirds, beaches for shorebirds.

The weather was brisk, the day bright. In the parking lot, I noticed a board on which were listed recent wildlife sightings.

"Eurasian Wigeon" said the board, and I walked over to the pond where a very prominent new member of my life list was on display, pretty much in splendid isolation, almost as if it were a duckie in a bathtub. It was not yet in eclipse plumage, so there was the beautiful chestnut colored head with the creamy forehead and crown above what some call a pink-brown breast. Really beautiful.

Such is the luck of the bird. I cannot count the times the luck ran the other way, and, as all birders know, it doesn't even out.

What is this Eurasian Wigeon? For one thing it has a more interesting scientific name than the American Wigeon. The American is Anas americana, the Eurasian

Anas penelope -- from Penelope, wife of Odysseus (Ulysses), it would appear.

Bulfinch's Mythology:

But Minerva, appearing in the form of a young shepherd, informed him where he was, and told him the state of things at his palace. More than a hundred nobles of Ithaca and of the neighboring islands had been for years suing for the hand of Penelope, his wife, imagining him dead, and lording it over his palace and people as if they were owners of both.

Penelope was one of those mythic heroines whose beauty was not that of person only, but of character and conduct as well. She was the niece of Tyndareus -- being the daughter of his brother Icarius, a Spartan prince. Ulysses, seeking her in marriage, had won her over all competitors. But, when the moment came for the bride to leave her father's house, Icarius, unable to bear the thoughts of parting with his daughter, tried to persuade her to remain with him and not accompany her husband to Ithaca. Ulysses gave Penelope her choice, to stay or go with him. Penelope made no reply, but dropped her veil over her face. Icarius urged her no further, but when she was gone erected a statue to Modesty on the spot where they had parted.

Romantic as all this may seem, some of the experts on names think that the use of "penelope" is just a mistake. Aristotle used "penelops" to refer to certain species of duck. The AOU Check-list gives Linnaeus as the author of the name "Anas penelope," but Edward S. Gruson in Words for Birds (1972) seems to say that Linnaeus followed Aristotle's usage and that it was some later ornithological transcriber (or perhaps some early European typesetter) who inadvertently changed this to "penelope."

What Aristotle actually says occurs in a paragraph where he lists web-footed birds. The bulk of the short paragraph is on the cormorant. After the cormorant: "Further there is the large goose, the little gregarious goose, the vulpanser, the horned grebe, and the penelops." (Historia Animalium. Book 8, ch.3, Translation by D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson, M.A., C.B., Professor of Natural History in University College, Dundee). (Common Shelduck and Egyptian Goose are candidates for vulpanser).

A new dictionary, Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names, says Penelope's name derives from the Ancient Greek words for "braid" and "appearance" -- and thus from the ruse of saying she'd marry one of the hundred suitors after her while Odysseus was off fighting Troy when she finished weaving the funeral shawl she was making for Odysseus' father, famously unweaving during the night what she woven during the day. (pp. 46, 296). But how can her name derive from something she was doing after she was born?

An online encyclopedia of mythology gives this:

Penelope's parents were Prince Icarius of Sparta and the nymph Periboea. Periboea hid her infant daughter as soon as she was born, knowing that Icarius had wanted a son. As soon as Icarius discovered the baby girl, he threw her into the sea to drown. However, a family of ducks rescued her. Seeing this as an omen, Icarius named the child Penelope (after the Greek word for "duck") and raised her as his favorite child.

mythencyclopedia.com/Pa-Pr/Penelope.html

It is easy to say that current usage shows how mistakes live on, but it is more interesting to comment on why they live on. They live on because science is like other human activities, not in a world of its own. There are trade-offs in science, just as there are in a business or in legislation or in your own life. Is it worth now correcting the name? That would be easy to do -- the next of the regular editions of the checklists which appear periodically as taxonomy changes (based on the scientific "literature" regularly published by researchers) need only contain one additional correction: " 'Anas penelope' corrected to 'Anas penelops'." But that would create question marks about all prior references to the scientific name of the bird. Every time a new researcher sees "penelope" in the literature, that researcher has to somehow verify that this is really what today we call "penelops," rather it just being a slight, but valid, difference in names. Is it better to keep "penelope," press on, and expend energy on more important tasks? That has been the thinking.

Subsequent to my seeing them, both were transferred (actually, transferred back) to the genus Mareca by at least one authority: B.C. Livezey, "A phylogenetic analysis and classification of recent dabbling ducks (tribe Anatini) based on comparative morphology". The Auk 108, 3 (1991): 471-507. But the two ducks remain americana and penelope.

Taxonomic change, a large part of the life sciences.

From change to range. The Eurasian Wigeon has an enormous range. It breeds in northern latitudes from Iceland to Kamchatka Island, south to northern Europe, central Russia, and Transcaucasia. It winters in much of this same area but also to northern and eastern Africa, Arabia, India, Malaysia, southern China, and the Philippines, appearing regularly all along our Pacific coast and on the Atlantic-Gulf coast from Labrador to Texas, and casually in Sri Lanka, Borneo, Celebes, Greenland, and even Hawaii. In migration it also appears regularly in "the interior of North America from the southern parts of the Canadian provinces south to Arizona, Texas and the Gulf coast." That solitary duck in New Jersey was not so much a wigeon as a molecule.

The Eurasian is a dabbling duck. The dabbling ducks are a group of ten genera and about 55 species of ducks, including some of the most familiar Northern Hemisphere species. They are in the duck, goose and swan family Anatidae, where together with the Diving ducks they make up the sub-family Anatinae.

"Dabbling" because they feed on submerged vegetation not by diving under the surface of the water, but by upending on the water surface. These are mostly gregarious ducks of freshwater or estuaries. These birds are strong fliers and northern species are highly migratory. Compared to other types of duck, their legs are placed more towards the centre of their bodies. They walk well on land, and some species feed terrestrially.

In science, change occurs not only in names, but in classification. The Old World duck, the Marbled Duck Marmaronetta angustirostris, which used to be included among the dabbling ducks, is now classed as a diving duck. Such is unlikely to happen to the Eurasian since its diet is well-known and does not entail diving. It dabbles for algae, pondweeds and eel grass. Seeds are usually avoided in favor of stems and leafy parts. The leafy parts of upland grasses and clovers are also eaten, as are insects. It eats gravel to aid digestion. Items like small fish and frogs, mollusks, and crustacea are seldom eaten by the Eurasian Wigeon.

The one I saw there at the tip of New Jersey must just have filled its stomach because the only thing it was doing was paddling around the pool a bit, waiting to be observed. I was happy to oblige.

Chapters are sometimes supplemented by notes. Click Random Footnotes to see.

Table of Contents

Home page ->For a listing of chapters that includes each bird's name, click on Random Footnotes.

All is journey, and in this case, 30 journeys. We can make these particular journeys riding webbook or ebook. The complete ebook, sans ads of course, is available now for

purchase: Click here.

The introductory web posting of the first two chapters is in full. Click Additional for other postings.

F.W. Benson

Birds treated, but not featured (see Photo Credits):