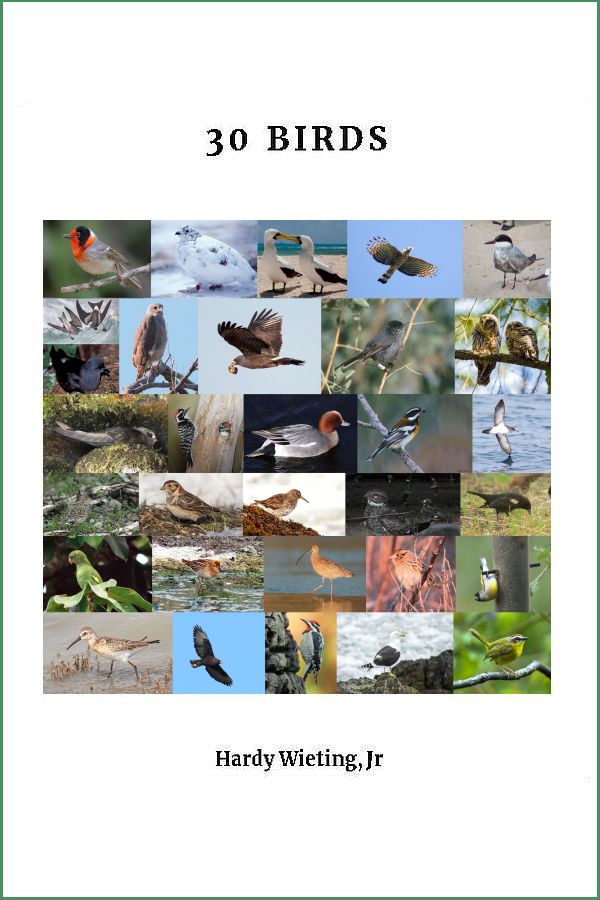

30 Birds

4/ On the Border

![]() ne Saturday in the first week of May, following a conference of our southern natural heritage programs held in the Texas Hill Country, I was birding with Larry Master and the brothers Hedges near Falcon Dam on the Rio Grande. I had already birded the Rio Grande Valley extensively on a previous trip, so to some extent my primary motivation for going along with Dr Master was that I had nothing else to do that day.

ne Saturday in the first week of May, following a conference of our southern natural heritage programs held in the Texas Hill Country, I was birding with Larry Master and the brothers Hedges near Falcon Dam on the Rio Grande. I had already birded the Rio Grande Valley extensively on a previous trip, so to some extent my primary motivation for going along with Dr Master was that I had nothing else to do that day.

It didn't take long for me to come to my senses and realize that this was an opportunity not to be missed: before long, I had seen two new birds on this second trip to the Rio Grande.

One of them was the Olive Sparrow, seen at a rest stop on the drive down; the other was the Clay-colored Robin, seen at our first stop after that, Bentsen State Park.

The Olive Sparrow comes to us from Central America, as far down as Costa Rica and Nicaragua. The bird is sometimes described as plain. But to me it gives the appearance of an immaculately clean and well-groomed bird, almost as if the grayish-tan feathers were hairs carefully brushed into place. There is no pattern, just the uniform grayish-tan, with olive undertones on sides and back and edges of tail. The thin brown stripe from the base of the beak, interrupted by the eye, then arcing down to the base of the neck is elegant, as are the brown crown stripes. One is reminded of the Green-tailed Towhee, but the rufous crown is lacking. Apparently, some ornithologists believe the Olive Sparrow should be considered a towhee, or very close to one. It forages on the ground, scratching its feet in the leaf litter.

The Clay-colored Robin which I saw back then is now the Clay-colored Thrush. Despite this name change, though, it retains its similarity to the American Robin, though as the name indicates, it is not so colorful. It ranges from eastern Mexico to northern Colombia but is now also a regular visitor to southernmost Texas, especially in winter, though it has also nested in Texas on at least one occasion. Very common in parks and gardens, it is the national bird of one Central American country, Costa Rica, chosen over the many spectacularly-hued birds there because of its familiarity. Its equally familiar American cousin, however, flies in the shadow of the Bald Eagle, and thus has not been so honored.

First, a bit of back-tracking. On this journey of pursuit, we were departing the Edwards Plateau and heading south. But it is impossible to leave the Edwards Plateau, of which the Hill Country is the eastern portion, without remarking both its extraordinary ecology and its extraordinary history, the two interlinked.

Basically, the plateau is a gigantic and well-defined aquifer occupying much of the middle of our largest of the contiguous states. It extends all the way from the Pecos River to Austin, about 100 miles wide and 200 long. It consists of limestone, a single massive block 600 to 800 feet thick. One source says the surface is "stream-dissected into a rolling terrain, which is honey-combed with caves and sinkholes throughout." To its west are the deep canyons of the Rio Grande and the Pecos River. To its south is the Balcones Escarpment. The surface found by the earliest settlers from the east was prairie, of which a tiny portion still exists in the arid far western share. The Hill Country in the eastern share is wetter, noted for its wooded hills, lovely valleys, and clear streams. The water collected in the limestone is slowly released along the plateau's edges. This becomes springs, streams, and underground water. Comanche Springs has a flow rate of 20 millions of gallons per day; San Felipe Springs has a flow rate of 65 million. These seem like large amounts, but both these flowed at twice these rates in the days before the plateau was overgrazed.

And that, together with the isohyet, is the link to the plateau's history. The best account of this that I know of is given in the first pages of the first volume of Robert Caro's massive series, The Years of Lyndon Johnson. He starts with the dreams of early settlers of this prairie, among whom Johnson's ancestors were included: "In country where grass grew like that, cotton would surely grow tall, and cattle fat -- and men rich." But an invisible line would prevent this, an isohyet, from the Greek for "equal rain." In essence, there is a line which divides the US into an area in which at least 30" of rain falls each year and an area where it does not, indeed where it rapidly diminishes in amount the further west you go. A source in 1921 quoted by Caro says simply that these two areas are characterized "one by a sufficient, the other by an insufficient rainfall for the successful production of crops by ordinary farming methods." This isohyet runs basically along the 98th meridian, and the 98th meridian basically runs along the eastern edge of the Edwards Plateau. The history of settlement of the plateau is thus one of failure after failure, failures which left the thin soils depleted and the shrub scrub which catches the eye today.

Few birders are aware of this, of course -- I certainly wasn't. Rather they are aware that the Edwards Plateau is a prime area for Golden-cheeked Warbler, Black-capped Vireo, and Cave Swallow.

Following a path through a low woods on the banks of the Rio Grande, at another place recommended in the guide books, we encountered some birders headed in the opposite direction. We told them about the Clay-colored Robin we had seen at Bentsen. They told us that they had seen a Hook-billed Kite at its nest in the abandoned Scout camp up ahead in the direction we were going.

The Hook-billed Kite, a good-sized raptor, is found over a very wide range, from northern Argentina to northern Mexico, and also in the Caribbean, including Grenada in the Lesser Antilles and Trinidad. The population on Cuba is in a different group (wilsonii v. uncinatus), and is sometimes regarded as a separate species.

It hardly ever appears, let alone nests, in the US. In the few times (possibly as few as two) it had nested in the US before this, it had done so in this same area, just across the Rio Grande in southern Texas. Although its range is extensive, I think I remember hearing that it is nowhere an abundant bird. Still, it was the thrill of adding this very rare visitor to the US to our list that immediately changed our plans and put us in pursuit.

One thing about the Hook-billed that intrigues me in particular is that although it will eat insects and small amphibians, it greatly prefers snails of various species. "A pile of broken snail shells beneath a tree may indicate a favorite tree or nest site above," says the guide. Perhaps this is how our trail companions located the bird.

This means that this bird, of the genus Chondrohierax, shares the tastes of its cousin the Snail Kite, of the genus Rostrahmus, although the Snail Kite -- a bird which was to bedevil me for years -- occupies the summit of monomaniacal eating habits, confining itself almost exclusively to one species, the Apple Snail. Similarly, the Snail Kite confines itself almost exclusively to freshwater tropical and subtropical freshwater marshes, whereas the Hook-billed Kite is a bird of the lowland forest, often in a swamp, but also in open woodland and much drier areas such as we were in here on the border between Texas and Mexico.

The abandoned Scout camp is an eerie place, the more so as the day readies itself for its ending. The stands of mesquite you walk through are shadowy, dark. The open areas between the mesquite stands are choked with chest-high grasses. There are no well-defined paths through the grasses, making it a struggle to cross from one stand to the next, almost as slow and as difficult as wading in chest-high water. The grasses are dry and tan even in early May.

There is an old wooden water tower in disrepair. It adds a forsaken note to the scene. The atmosphere suggests illegality, even though happy Boy Scouts once played in these fields. No one has been here in quite some time, however, and no one is here now in the late afternoon -- except for three birders (one of the Hedges brothers decided to forego this particular kite chase).

We walked Indian file, Larry in the lead. I was right behind him. The kite is a wary bird. We tried to make as little noise as we could. We walked for what seemed like a very long time, without hearing or seeing a thing. The light was fading.

Several times, just as we emerged from the darkness of a stand of mesquite into one of the clearings, Larry thought he had seen the kite fly away from us. I had seen nothing. I had heard nothing. After the third or fourth time, I was beginning to think that Larry was making this up and that we were pursuing a ghost.

This seemed more and more likely as the light faded and the camp grew eerier and eerier.

Just when we were about to give up, however, we noticed a large nest within one of the bigger stands of mesquite. The nest was empty. We had to make an investment decision. If this was the nest of the kite, and we invested our time in waiting for a bird that in fact returned in the coming minutes -- perhaps as many as a half hour or so -- we would reap a reward and pat ourselves on the back for our skill in the market. On the other hand, if this was not the nest of the kite or the kite did not return until after dark, we would be bankrupting ourselves by investing our time here.

Knowing about the snail shells would have made the decision a lot easier, no doubt. But I knew nothing of the dietary habitats of the Hook-billed Kite at that moment. I personally had never even heard of the Hook-billed Kite before those guys on the trail had mentioned it, though Larry knew instantly of its importance. This was probably not just because of his vast general knowledge of birds, but because he had done his homework before taking this trip to Texas -- Dr Master always does his homework. Whether this homework included the data about the snail shells I do not know. I do know that we decided to wait.

We waited in absolute silence for the bird to return. Time passed slowly. Although light and time are directly related, of course, it seemed that the light was fading faster than the time was passing, and our concern about whether there would be enough light for us to see anything deepened as the seconds ticked by. Suddenly, I don't know how, we sensed that the bird was returning. Three pairs of binoculars were raised in unison as a Hook-billed Kite landed, without a sound, on the nest.

![]()

Chapters are sometimes supplemented by notes. Click Random Footnotes to see.

![]()

Table of Contents

Home page ->For a listing of chapters that includes each bird's name, click on Random Footnotes.

All is journey, and in this case, 30 journeys. We can make these particular journeys riding webbook or ebook. The complete ebook, sans ads of course, is available now for

purchase: Click here.

The introductory web posting of the first two chapters is in full. Click Additional for other postings.

F.W. Benson

Birds treated, but not featured (see Photo Credits):