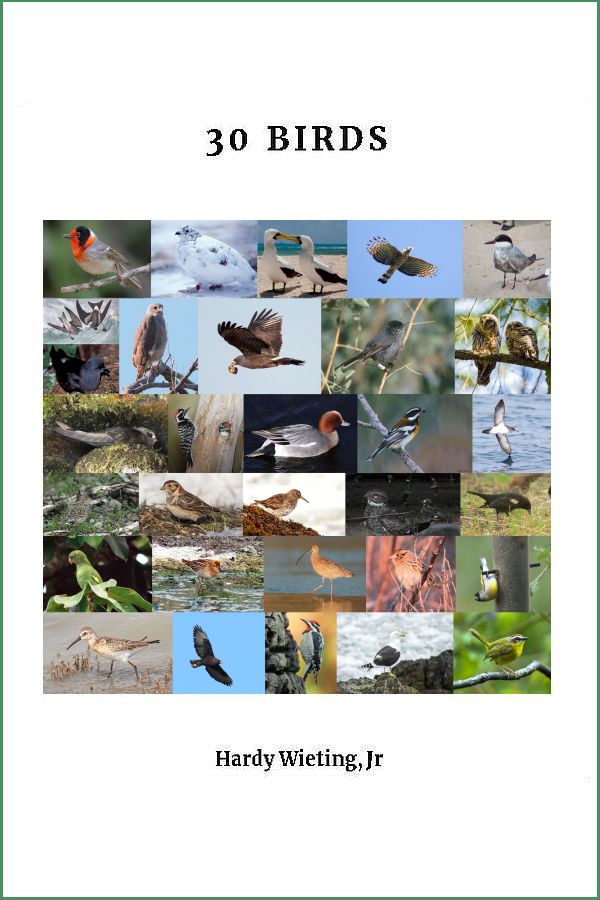

30 Birds

1/ Irresistible Lemmon

![]() or several springs before I actually caved in and took up birding, Dr Chipley

had been encouraging me to join him on his short walks at lunchtime over to Theodore Roosevelt Island, which sits in the Potomac River between the Kennedy Center (and Watergate)

and Rosslyn, VA. The spark that kindled the shift in my response had sparked in the rain: visiting friends (from Korea) in New Jersey one drizzly weekend that March, we decided to spend

the dark afternoon at Brigantine National Wildlife Refuge -- it was something to do, out of the ordinary. We proceeded at a snail's pace along the Wildlife Drive. At one point we slowly

passed a very wet Great Blue Heron standing tall aside the drive, illuminated in our headlights -- "What a bizarre and fascinating creature!" thought I. Those first trips out onto TRI ignited

a passion. The first bird glorious I saw out there was the Black-and-White Warbler. I found it myself by plunging into the brush, but had to ask my companion to identify it, which he did on

the basis of my description of what I was seeing. "It's landed on the trunk and is moving up" . . . and so on.

or several springs before I actually caved in and took up birding, Dr Chipley

had been encouraging me to join him on his short walks at lunchtime over to Theodore Roosevelt Island, which sits in the Potomac River between the Kennedy Center (and Watergate)

and Rosslyn, VA. The spark that kindled the shift in my response had sparked in the rain: visiting friends (from Korea) in New Jersey one drizzly weekend that March, we decided to spend

the dark afternoon at Brigantine National Wildlife Refuge -- it was something to do, out of the ordinary. We proceeded at a snail's pace along the Wildlife Drive. At one point we slowly

passed a very wet Great Blue Heron standing tall aside the drive, illuminated in our headlights -- "What a bizarre and fascinating creature!" thought I. Those first trips out onto TRI ignited

a passion. The first bird glorious I saw out there was the Black-and-White Warbler. I found it myself by plunging into the brush, but had to ask my companion to identify it, which he did on

the basis of my description of what I was seeing. "It's landed on the trunk and is moving up" . . . and so on.

Three months after this, I had seen quite a few birds for my new life list, and I was in southern Arizona in pursuit of another warbler, one which cannot be seen back east, one which is extremely attractive, and one for which a friend of mine named Scott Mills who lives out here and works as a zoologist had mapped out for me. This was the Red-faced Warbler, and the map was a Xerox of a topographic map of the road up Mount Lemmon, outside of Tucson. He listed on the map, using a red felt-tipped pen, all the birds I could see on the drive, starting at the top:

R.F. Warbler

Mountain Chickadee

Western Flycatcher

B.T. . . .

Grace's Warbler

Olive Warbler

Pygmy Nuthatch

Coues Flycatcher

Painted Redstart

V.G. Swallow

D.T. . . .

Northern Raven (Any)

E. Bluebird

Mountain Chickadee

Arizona Woodpecker

Verdin

Cactus Wren

C.B. Thrasher

[Crissal Thrasher]

B.T. Gnatcatcher

Phainopepla

Hooded Oriole

B. Towhee

R.C. Sparrow

As if that weren't sufficient, he also listed six birds that could be seen in nearby Sabino Canyon, all of which are found on the above list as well.

Yes, the Red-faced Warbler was at the top of Mount Lemmon. It also was at the top of the list of birds I wanted to see. Who can resist a red face? I was going to start at the top and see the other birds on the way down.

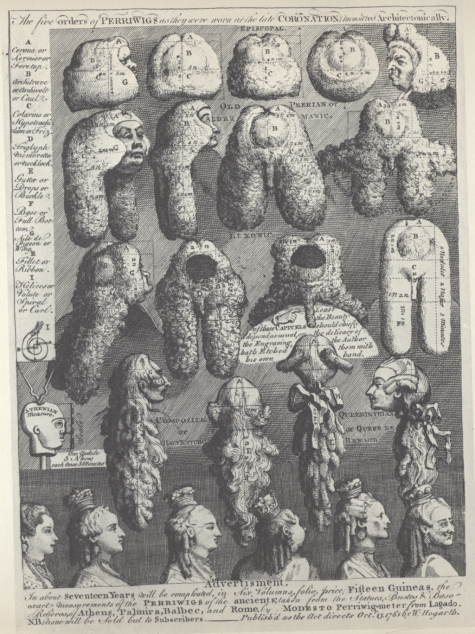

That red face, to be sure, is not the whole story, even of the bird's head. Behind the red is dark black which one guide calls a cap, another a crown, a third a bonnet,

though in all cases it is added that the black extends down the cheek and is accompanied by a small white patch behind. The effect is striking, on that everyone agrees. To my mind, the

black recalls a periwig, more specifically something from the top row of a painting by Hogarth, "Five Orders of Periwig," which I stumbled upon in researching this. The effect is striking, on

that everyone agrees. The back is gray, the underside white, both of which serve to emphasize what is in front of them.

The American Bird Conservancy made the Red-faced its "Bird of the Week" not long ago. This was part of ABC's description of the bird:

During breeding season, pairs of Red-faced Warblers maintain an all-purpose territory where both male and female feed. The male establishes, defends, and advertises the territory; the female also defends the territory against other females.

Although this species appears to be typically monogamous (a single pair maintains and defends a territory), the birds engage in high rates of “extra-pair” activity. Neighboring males often sneak onto established territories to copulate with females of other pairs, and females occasionally leave their territory seeking other males. In fact, almost three-quarters of nests contain a young bird fathered by a male other than the territory owner.

Perhaps the red has something to do with this. The only other warbler with red, incidentally, that we see anyway, is a bird which used to be placed with the Redstarts, but is now placed with the Whitestarts (South America), though the old name is still used. The Painted Redstart has black plumage with red lower breast and belly.

Both are birds of the mountains and have very similar ranges. This range is centered along the mountains that run down the center of Mexico, with extensions at both ends. To the south, in winter, the Red-faced's range extends through Guatemala and El Salvador into Honduras. To the north, in breeding season, the range extends across the border as far as north-central Arizona and far west New Mexico, almost to I-40. This northward extension is increasing, apparently due to logging in Mexico. I gather from several sources that the Red-faced does not like logging.

The bird often forages in towering trees (summer males singing as they do so), so it is a surprise to find that it builds its nest on the ground. It hides the nest under shrubs

or tufts of grass, at the base of boulders or a tree trunk, or under a log. The female is the builder. She constructs the small cup out of grasses, weeds, bark, lined with plant fibers and hair.

Both parents feed the fledglings, though they sometimes divide the brood into two groups, one parent responsible for one of the two. Is this unusual division related in some way to the

"extra-pair" activity?

Take your pick: Catalina Highway, Mount Lemmon Highway, General Hitchcock Highway, Arizona Forest Highway 39, Sky Island Scenic Byway. They are all in essence the same road leading up from the outskirts of Tucson to the top of Mount Lemmon at 9,000 ft. The last of these names nowadays is being given prominence because of the designation by the Federal Highway Administration. The name matters not because the drive is gorgeous.

Years later, through friends who live in Oracle, I became acquainted with -- and took -- the dirt road that leads up along what is now known as the back of the mountain to the top of Mount Lemmon. Oracle, which lies between Tucson and Phoenix (though it is much closer to Tucson), is today a funky place with a history as a resort to which people with tuberculosis would go (the father of the famous sculptor, Alexander Calder, was one). For many years, apparently, this was the only road to the top. It is perfect for 4-wheel-drive vehicles, but other vehicles can manage its twist and turns as well.

By 1933, however, during the height of the Depression, this was not good enough. Frank Harris Hitchcock, a very distinguished Ohioan who had (like so many Midwesterners) moved to Arizona, and who was (like so few) a former Postmaster General, had a plan. To me, the interesting thing about Hitchcock is that he had a love of birds. He had studied at Harvard with the goal of preparing to be a lawyer and there had the good fortune to meet Teddy Roosevelt, another bird lover, one who wrote papers about the coloration of pigeon feathers. This friendship led eventually to his becoming chairman of the Republican National Committee in 1908 and then to becoming Postmaster General under William Howard Taft 1909-13. In Arizona two decades later, he laid plans for a new highway to the top of Mount Lemmon, a paved highway. Eventually, funding was secured.

Labor was needed, a lot of labor. What better source than guys in prison, with so little to do? And since Hitchcock was well-connected federally, a federal prison camp was established at the foot of the mountains. Eight years later came Pearl Harbor and the fateful decision to confine American citizens of Japanese descent living on the West Coast in internment camps. The federal prison camp now became an internment camp; internees were forced to labor on the highway that now leads up to the Red-faced Warbler. An attempt was made in 1999 to make amends for this injustice when the site of the camp was converted into a Recreation Area and named for one of the internee-laborers, Gordon Hirabayashi. (Unbelievably, he had had to hitchhike to the camp). Hirabayashi, later a sociologist (as opposed to a socialist), had been convicted of violating a curfew imposed by the Executive Order behind all this. His case went to the Supreme Court where he lost, of course. His case was overshadowed by the subsequent Korematsu v. US in which the Court upheld all aspects of the internment.

The highway which resulted from all this free labor was in many ways not much better than the original road up the backside. When you were not noticing the extreme

drop-offs along the narrow roadway as you climbed, you noticed the bumps created by pothole repairs. The highway enters Coronado National Forest and with funding from the US Forest

Service and Pima county improvements (including guardrails) were made beginning in the late 80s and culminating in 2007.

The drive up begins in Sonoran Desert landscape dominated by giant, attractive, distinctive saguaro. One source says that since you end up in shady conifer forests where there is snow in winter, even a ski resort, the drive takes you through "biological diversity equivalent to a drive from Mexico to Canada in just 27 miles." Another says that there are five separate ecological zones on the way up. My guess, though, is that travelers, even if they are not like me in pursuit of the Red-faced Warbler, are most impressed by the towering rock formations on either side of the highway. These are spectacular. Hoodoos they are, gigantic rocks piled on top of each as if by a god. At mile marker 15 there is Hoodoo Vista.

Mount Lemmon is part of the Santa Catalina Mountains, and as you rise higher you are rising along the southern flank of that chain. I could not help being bowled over by all this -- much (though not all) of my previous experience of southern Arizona was along flat land through which the San Pedro River flows -- but on this particular quest I was looking for a side road near the top which would take me into conifers where I had a good chance of seeing the Red-faced. The Xeroxed topo Scott had given me shows that near the top the highway makes a last and particularly sharp hairpin curve. From the very apex of this hairpin a side road leads straight to the wonderfully-named Bear Wallow Spring area.

I found this road and entered an area of tall conifers running up the steep slopes on either side. There was no other traffic, even though it was the middle of the day. Just silence and trees and mountain. I parked my car, grabbed my binoculars and went hunting. I strolled around, heard warbling. I did not have a tape recording or anything so artificial. I pished. This had worked for me with warblers back east, so I tried it. Immediately, I saw a single bird way up the slope to my right, high in the trees, working its way down from branch to branch to inspect this curious outsider. Yes, it was the Red-faced Warbler.

I presumed it had come to say hello, so wonderful was our meeting. The Red-faced Warbler looks all the more attractive for being set off against the shade cast all around by the giant trees, turning the needle-covered slopes dark. My thoughts ran to philosophy, how the small can dominate the large. My new friend was in no hurry to depart and flew from one tree to another close by for several minutes, looking me over. The red face stands out. Who can resist a red face?

At this point I broke out into laughter at the glory of it all: just the two of us, me and this endearing, beautiful creature I'd traveled so far to see relating to each other

in a dramatic setting on top of a mountain in the midst of an enthralling environment. That, plus the inkling there would be other moments like this in the future.

The Five Orders of Perriwigs as they were Worn at the Late Coronation Measured Architectonically. William Hogarth 1761.

Chapters are sometimes supplemented by notes. Click Random Footnotes to see.

Table of Contents

Home page ->For a listing of chapters that includes each bird's name, click on Random Footnotes.

All is journey, and in this case, 30 journeys. We can make these particular journeys riding webbook or ebook. The complete ebook, sans ads of course, is available now for

purchase: Click here.

The introductory web posting of the first two chapters is in full. Click Additional for other postings.

Birds treated, but not featured (see Photo Credits):