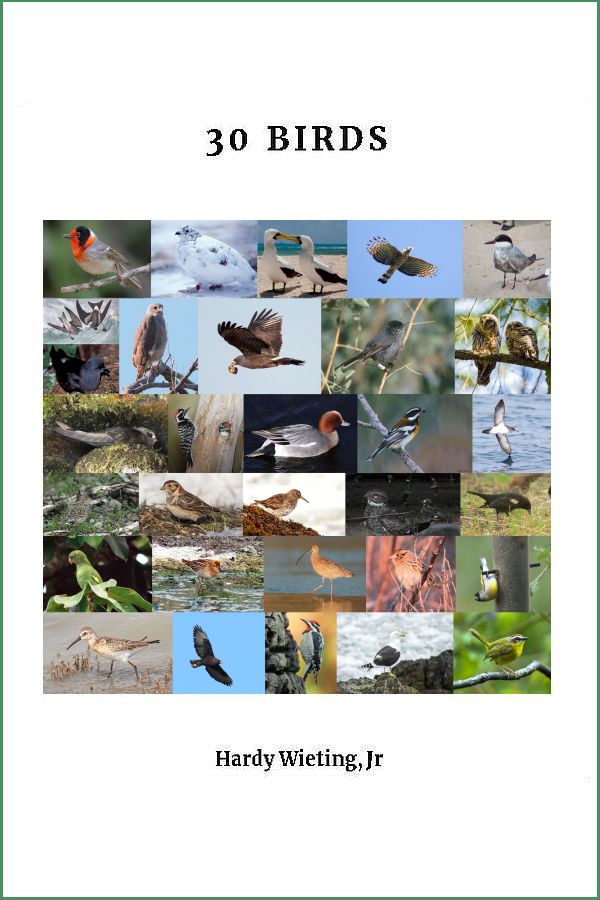

30 Birds

3/ Masked Sibilicide

![]() ospital Key. I could see it with my scope -- a tiny place, just some sand rising from the sea, except for what appeared to be one very small central knob of low vegetation. There seemed to be activity there, but I couldn't really tell for sure. Perhaps I was just seeing gulls flying low over the water between me and the key. Curious name: Hospital Key. There certainly has never been a hospital, or any building, there.

ospital Key. I could see it with my scope -- a tiny place, just some sand rising from the sea, except for what appeared to be one very small central knob of low vegetation. There seemed to be activity there, but I couldn't really tell for sure. Perhaps I was just seeing gulls flying low over the water between me and the key. Curious name: Hospital Key. There certainly has never been a hospital, or any building, there.

I was looking for the Masked Booby. I had come to the Tortugas to see the Brown Noddy and the Sooty Tern primarily, but also the Masked Booby, if there were any out there on that small, distant bit of sand. From Fort Jefferson, the best view of Hospital Key is from the old coaling dock, but "best" is a relative term -- in fact, it was not a very good view at all because Hospital Key is too far away, at least for my scope.

There would be one other chance. On the flight back to Key West, the small seaplane that had gotten me out to the Tortugas would fly near Hospital Key.

Masked Boobies lay one or two eggs. If two, the older chick has an advantage: it is larger and better able to coordinate itself. It uses this advantage to kill its sibling. It does this by ejecting its sibling from the "nest" (little more than a depression in the sand surrounded, prettily I imagine, by a circle of pebbles or other debris). The ejected bird is then prey for frigatebirds or for land birds or even for crabs. The parents do not attempt to defend the doomed sibling.

Primogeniture with a vengeance!

As such, this species is of uncommon interest. Each species is thought to be programmed to seize every opportunity to propagate itself, to pass its genes on to the next generation. The result of this programming, which takes place, according to the modern view, at the level of genes themselves, is that species are involved in a struggle for survival. Effective propagation is essential if the species is to win this struggle, indeed if it is not to vanish completely, either suddenly in a single generation or slowly over a number of generations. Yet Masked Boobies have evolved a pattern of behavior which seems, on the face of the matter, to reduce by half the chances of effective propagation.

Siblicide is not confined to Masked Boobies, but is generally found only in certain seabirds and, to a lesser degree, among birds of prey. There are, moreover, variations on this particular behavior: eg, ejected kittiwake chicks wander over to other nests and kill the unattended chicks or eggs they find there and attempt to be adopted, sometimes successfully. Siblicide is not always a case where the older kills the younger; the younger will kill the older if it can, and occasionally it succeeds.

What can account for this behavior? Scientists abhor vacuums, so there is no lack of theories to explain it. One theory has it that Masked Boobies are not able to supply food to more than a single chick. The theory is that they lay a second egg in case the first does not hatch (not unusual, since only 60% of Masked Booby eggs hatch), but that since they can forage enough food for only a single chick they do not interfere if one chick kills the other. Nice theory. However, the closely-related Blue-footed Booby can raise three chicks and regularly raises two. The foraging techniques and abilities of the two species are not different enough to account for the discrepancy in the number of the chicks the two species raise. Moreover, in cases where scientists have lifted the hand of mercy and prevented siblicide, Masked Boobies have successfully reared two chicks, and Masked Booby populations are significantly greater than in cases where this has not been done.

The controlling idea behind the theorizing here is that Masked Boobies must have evolved siblicidic behavior in order to increase their chance of reproductive success. If there were a limitation in their ability to feed two chicks, then the idea of an "insurance egg" makes sense, for should something happen to the first born, the second could survive to adulthood. Siblicide on this theory would be a way of establishing the survivability of the one chick that can be effectively nourished. But if Masked Boobies can rear two chicks, if there is no limitation in their ability to do this, and indeed if they have done so successfully in situations where siblicide is experimentally suppressed, then the theory breaks down.

Here is another theory, this one put forward by the same ornithologist, David J. Anderson, who helped demolish the first. The siblicide of the Masked Booby reflects ancient requirements singular to Masked Boobies, now outmoded but impossible to reverse. At one point in the past, their food was in fact limited (or some other limitation was in operation), so that only one chick would survive. Siblicide evolved in response. This limitation no longer exists, but the two chicks are caught in something like the "prisoner's dilemma" -- the famous example from game theory in which two murderers are captured by the police and taken to separate rooms for interrogation. The police have a weak case, but a clever strategy. They offer each prisoner a deal: "confess and we'll be lenient; if you don't confess, we'll see you get the electric chair." This puts A in a dilemma. If he holds his tongue, he may go free, but he takes a very great risk -- for if he says nothing, and B squawks, then it's the chair. B has the same dilemma. The rational course seems to be to confess (a life sentence), even though if both clam up, both will go free. Neither A nor B can afford the risk of remaining silent. Similarly, neither Masked Booby chick can afford the risk of abandoning siblicide. Each is without knowledge of what the other will do. In these circumstances, the natural course is to get rid of the risk -- kill your sib.

Siblicide is only one of the fascinatingly grisly aspects of the life of the Masked Booby. There is also bloodfeeding.

Bloodfeeding is something that happens to certain boobies in the Galapagos (recently split off from the Masked Booby as the Nazca Booby). Small land birds there -- two species of the famous Darwin's finch, one of them called the vampire finch, and a mockingbird -- have been observed pecking at wounds on the neck or at the base of the tail of boobies. Blood flows down the neck or over the rear of the booby. This pecking at the blood flow produces gruesome scenes of blood-soaked boobies. This phenomenon is most prevalent in dry years. Rain calls it to a halt.

Again, scientists have produced theories to explain this. One theory is that boobies suffer from lice, so perhaps they permit the smaller birds to peck at them in hopes that the smaller birds will also eat the lice.

For all these grim behaviors, all boobies are humorous creatures that well deserve their name, which is derived from the Spanish and Portuguese bobo for "dunce" or "buffoon." They are sometimes seen riding on the backs of sea turtles swimming in the ocean; they can even sleep in this position. On land, they swagger amusingly when they walk, like John Wayne on his way to a drawing contest. When they nod off in the presence of mosquitoes, they slap their feet against the ground every half minute or so, possibly to shake the mosquitoes free. They allow humans to approach and show no fear. They are headshakers. They advise others of their territory by "nodding a violent Yes superimposed on a slow No." (J.B.Nelson, The Sulidae, 1978). They are beakfencers. The hollow clap of beak against beak can sound serious, and often is, but more often the fencers retire before permanent damage is done.

Courtship is particularly amusing and attractive. Males point their bills straight up, stretching their necks, as a means of attracting females. Couples stare directly into each others' eyes for prolonged periods, more intently even than a teenage couple sharing a malted milkshake at the local soda fountain. One booby will pick up a feather or a pebble and parade around with it for the other, ceremonially lifting one of its webbed feet high off the ground, taking a step, then lifting the other in a measured cadence. The gift is then presented to the partner. All this produces a strong bond, for Masked Boobies are not only monogamous: they don't fool around either.

Although some breeding colonies of booby are large and dense, such as the ones in the Galapagos (where there are perhaps 25,000 pairs or more), most are small. In 1990, the islet of Lekua in the Hawaiian Islands had but five to ten pairs.

The colonies are far-flung. Imagine a committee appointed by the First Lord of the Admiralty, charged with suggesting places for the exile of Napoleon. The committee makes its report:

"Milord, the list is as follows: Cocos-Keeling, the Chagos Archipelago, the Mascarenes, and Cosmoledo Atoll, in the Aldabra Group in the Indian Ocean, the Ryukyus, the Kermadec and Tuamotu Islands, Kaula Rock and Moku Manu in the Hawaiian chain, Clarion Island and Clipperton Island in the Pacific off Mexico, Cayo Arcas in the Gulf of California, the Galapagos, Isla San Ambrosia and Isla San Felix off Chile, Santo Domingo Cay in the southern Bahamas, Pedro and Serranilla cays southwest of Jamaica, Monito Island off Puerto Rico, Cockroach and Sula cays in the Virgin Islands, Dog Island off Anguilla, Islas de Aves off Venezuela, Ascension Island and St. Helena in the south Atlantic, Boatswain Bird Island in the central Atlantic."

The committee would basically have described the breeding range of the Masked Booby. It should be added, though, that pigs, goats, rats, cats and dogs had eliminated the Masked Booby, even by 1815, from the island included on this list that was ultimately chosen. Napoleon's isolation was thus complete.

Masked Boobies are of the essence of the tropical seas. Their close relative the gannets (the world has three species of gannet, six, now seven, of booby) nest as far north as the islands off the Gaspé Peninsula and Iceland. But the Masked Booby does not nest beyond 30 degrees N or S and seldom beyond 25 degrees (Hospital Key is not quite 25 degrees). Gannets migrate, but Masked Boobies stay where they are, though occasionally they vacate the breeding colony.

This affinity to the tropics is matched by their affinity to the ocean. They not only do not drink fresh water: they refuse it when it is offered. They partake, instead, of sea water. They have glands in depressions above their eye sockets that filter out the salt. A hypersaline solution trickles from these glands, through their nostrils -- which are internal nostrils in the roof of their mouth -- down to the tip of their bill.

Their diet, too, is marine. They eat flying fish, sardines, squid -- diving down from as high as 30 or 40 feet into the ocean where, under water, they seize and swallow prey. Rising again into the air, they are sometimes marauded by frigatebirds, who use their bills to grab the booby by the tail. The booby responds by disgorging what it has caught. The frigatebird then catches these fish as they fall through the air.

I was seated at the right window in the middle of the small plane. I had a clear view of the ocean, particularly when we dipped to the right. We circled around as the plane gained altitude, and then the plane dipped to the right for a second time. I got my binoculars up and on the key.

Below me, I could see one bird landing -- wings outstretched, black trailing edge, booby-shaped, just like the NGS illustration. I had an overriding impression of white: white beach, white boobies. One or two of the boobies already on the key were looking up, perhaps noticing the plane, perhaps dancing for each other. Then I saw three more gliding over the water, narrow white shapes in close formation, approaching the beach to land. Altogether I saw nine birds at most, maybe only a half dozen. The pilot, rightly, did not want to sweep too low or to harass the colony. So, this brief (but satisfying) look was all I was permitted, and we continued on our way back to Key West.

Nearly fifteen years later I attempted to see another booby, the Brown Booby. If you exclude the two outlying states admitted in the fifties as a pair, in a compromise between our two major political parties, this Brown Booby was about as far away from Hospital Key as you can get and still remain within the United States of America.

The Brown Booby occasionally ranges far up the western coast of North America, crosses the Mexican border, and appears as far up as Monterey Bay. Some say it is a sign of an El Niño year. The hotline told me this had happened, in December, told me repeatedly over a series of days before I could find a time to go. Accordingly, eventually, my eleven-year-old daughter and I made our way on a sunny but windy day to the Coast Guard breakwater in Monterey. The breakwater is in fact a rocky jetty populated by cormorants mainly, and gulls, the usual suspects, but it is also locked off by a tall wrought-iron fence. Binocular inspection is possible between the bars, but it proved to be of no avail. We met a woman with binoculars of her own who asked us if we were looking for the booby. “We surely are, but we’ve had no luck.” Later, over by Fisherman’s Wharf, we met a man with a scope. He was from Idaho, but was birding California on vacation. This was his last day. He had seen the booby a few days ago. It was beautiful.

On several other occasions, while the bird was still being reported, I took up a position windier and much colder at the end of the Municipal Wharf. There are two wharves in Monterey, very close to each other. By far the better known is Fisherman’s Wharf, a much smaller version of San Francisco’s, but also consisting mainly of seafood restaurants and souvenir shops. The other wharf is Municipal (aka Commercial) Wharf, a working center for the seafood industry on this part of the bay. It stands closer to the spot commemorating how Teddy Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet hove into view in. One account I have read of this says:

The Fleet of 16 battleships arrived in Monterey Bay from Santa Barbara on Friday, May 1, 1908. It was welcomed by large crowds of people and communities in Monterey. Mayor Will Jack took two-hundred officers on the 17 Mile Drive and Pebble Beach. The Second Squadron staying in Monterey, after a day in Monterey the fleet was dived with the first squadron going to Santa Cruz. In the evening the Hotel Del Monte (now the Naval Postgraduate School) was host to a grand ball. On May 4th, the Second Squadron and the Torpedo Flotilla left Monterey and joined the First Squadron in Santa Cruz. And left for San Francisco on May 4th on its 14 month round the world trip.

The far end of Municipal Wharf provides a good view, from across open water, of the Coast Guard breakwater where the booby had been seen. A boat or two, anchored but bobbing in the choppy water, interfered with the view, but not much. The booby clearly wasn’t there, or was ensconced on the far side of jetty, out of view.

How is this booby different from its cousin, other than being so far away here in the northern extreme of its range? The Brown Booby differs in that it constructs a nest on the ground, unlike the Masked which utilizes a slight depression in the sand or sandy soil. The Brown’s nest is a mound opportunistically created out of whatever seems available, natural (branches, bones, grass) and unnatural (trash). Like its cousin it mainly feeds on fish, naturally, especially flying fish, which must be quite a catch, and squid; but its nests have sometimes been found to contain the bodies of dead Sooty Tern chicks, though whether this is a rejected food item or punishment for errant behavior by infants I don’t know. (The Brown like the Masked is comical in many respects, but also siblicidic). The nests, at any rate, are in colonies grouped together in the open on islands almost anywhere in Oceania in the area from 30° N latitude to 30° S latitude.

The Brown Booby used to predominate at Midway, before the famous battle. Rats, not dive bombers or torpedo planes, did them in; but there is good news: the rats have been eliminated and nests have started again to appear.

Imagine flying over the sea at a height (sometimes) of a five-story building and then suddenly plunging straight down into the water – and you can see in your mind how the booby hunts. Remarkably, just before entering the water the wings, which have been tucked next to the body for speed on the dive, are raised straight over the body, touching each other as booby penetrates sea. The dive is not particularly deep, about as deep as I am tall, and presumably the raised-wing entry enables the immersed booby to push down on the water (rather than the reverse) and return to the air in one smooth motion. All this is usually being conducted where tuna, or some other predator, has herded flocks of smaller fish near the surface, or in the wake of a fishing vessel.

A couple of weeks passed. Then the emails said “Santa Cruz.” A Brown Booby had been sighted at Natural Bridges State Beach sunning itself on the rocks visible from the Overlook Parking Lot at the entrance to the park. I hastened to find it the next day, arriving about 9 in the morning. The coast all along Northern California is often socked in by what used to be called fog and which is now called, more accurately, “the marine layer,” an interesting condition caused by the extremely deep and extremely cold water immediately offshore. But today the marine layer was lying out to sea and visibility was good, though there was a thin overcast.

Natural Bridges State Beach is at the end of West Cliff Drive, an elevated seaside street lined with houses on the land side and cliffs and rocks and a beautiful view of the Pacific on the ocean side. I drove into the parking lot, set up my scope, and looked over. But there was no booby. I scouted around. But there was no booby. What I found oddest, however, was that I was the only birder there. A couple of other cars pulled in while I was there, but they proved to contain tourists, out for a look at the natural bridge, the off lying rock island with the small arch you could perhaps swim through if you were a polar bear.

A Rock Sandpiper had also been seen along West Cliff Drive. I went in pursuit of that. I had tried for the sandpiper about a week before, but all I could find were Black Turnstones. Nonetheless, hope springs eternal, so I was off.

Without success. When I returned, about an hour later, there was a guy with a scope and another car, closer to where I pulled in, the occupant of which had just alighted from his vehicle and was working on pulling out his scope from the back seat. He asked me if I wanted to see the Brown Booby. “Where?” said I. “Right there,” said he, pointing to the top of the natural bridge to a lone bird in full sun.

He was correct. The bird had its back to us, so we could not see the white belly, but otherwise it was all there, including the blue facial skin at the eye. He very kindly asked if I wanted a better view through his scope, and I said yes.

![]()

Chapters are sometimes supplemented by notes. Click Random Footnotes to see.

![]()

Table of Contents

Home page ->For a listing of chapters that includes each bird's name, click on Random Footnotes.

All is journey, and in this case, 30 journeys. We can make these particular journeys riding webbook or ebook. The complete ebook, sans ads of course, is available now for

purchase: Click here.

The introductory web posting of the first two chapters is in full. Click Additional for other postings.

Birds treated, but not featured (see Photo Credits):