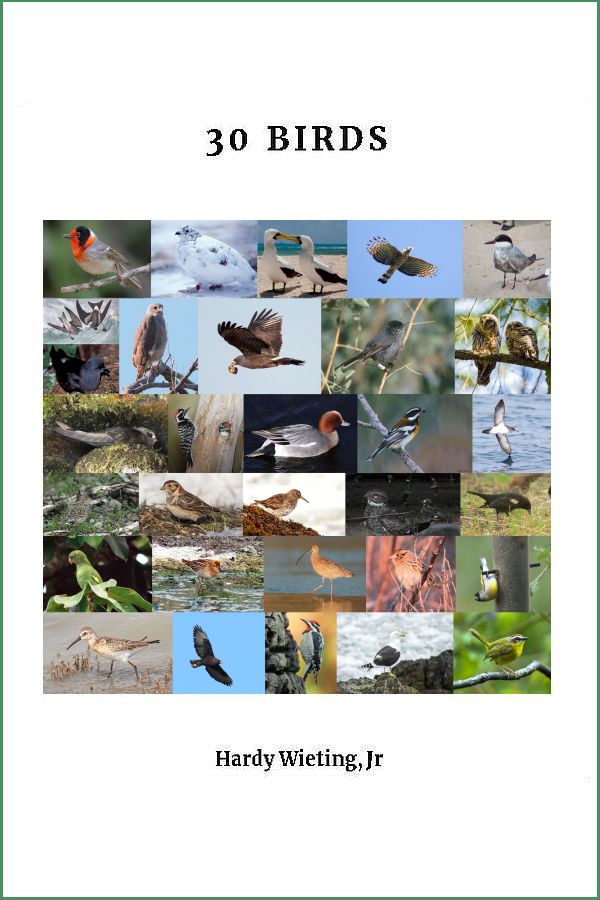

30 Birds

7/ Contented Hog

There is a curious passage involving a raptor in Simon Schama's curious, interesting, magnificently-written book, Dead Certainties, in which he adverts to the friendship between George Parkman and John James Audubon.

George Parkman was a Boston Brahmin and uncle of America's most famous historian, Francis Parkman, best known as chronicler of the Oregon Trail, Pontiac, Montcalm and Wolfe, and the North American forest. George Parkman was murdered by a Harvard professor, John Webster on November 23, 1849, yet another whack to the corpus of town-gown relationships in that part of the world. Schama's book is, in main part, about that murder.

The raptor in Schama's book possesses a dignity which is possessed by all birds in that group, except perhaps buzzards, but which reminds me especially of a hawk I saw in a part of America which is about as far from Boston as you can get and still remain on the continent.

George Parkman, himself a graduate of Harvard Medical College, was an eccentric figure, even in a city of eccentric figures. His Grand Tour had taken him to France in 1811 where he, like so many other wealthy Americans, had met the Marquis de Lafayette. Much more eccentrically, he had been welcomed into the home of Benjamin Thompson. Thompson had known George's father when as young men just starting out they both worked in the same dry goods store in Boston. But Thompson was a Loyalist and so now lived in Auteuil, suburb of Paris, after having resided in London and Bavaria. Schama delightfully writes that Thompson "had metamorphosed into 'Count Rumford' (a pumpernickel pedigree), inventor, landscape gardener and social engineer" and that he now "lorded over the villa that had once belonged to Antoine Lavoisier, the greatest of the old regime's chemists, a man of humanity and intelligence who had been guillotined as a tax farmer in the Terror." Thompson had been briefly married to Lavoisier's widow.

In this villa, "filled with the broken optimism of the scientific enlightenment," Parkman hobnobbed with some of the most eminent scientists of the day, including Cuvier, the great zoologist of whom Ernst Mayr said, "No one in the pre-Darwinian period produced more new knowledge that ultimately supported the theory of evolution," yet he was "wholly opposed to the idea of evolution." He also met Philippe Pinel, a doctor with progressive ideas on the insane and the asylums to which they were confined. George Parkman was most impressed with Pinel and his ideas and came back to America fired with the motive of attempting to implement them in his home country.

But George Parkman's efforts to implement these ideas and to become at the same time the head of a progressive asylum failed, and so he used the family's money to speculate in real estate, acquiring (according to a contemporary account quoted by Schama) "cheap built tenements let at high rates and as he is his own rent collector and keeps no horse is seen moving through the city." Schama calls him, however, no mere real estate speculator, but "a man of passions and mysteries, medical, literary and zoological."

For two days in bitter February 1834, he had worked with John James Audubon, coats off, desperately attempting to suffocate a golden eagle with charcoal and sulphur fumes so that the ornithologist might sketch it without plumage disfigured by the gun or the knife. But while the thick, yellow vapours sent the men choking and rushing for the door, the great bird sat erect on its perch, its eyes glinting, body defiantly and resolutely alive. Despairing of any other solution, father and son Audubon resorted to the usual execution; one tethered the bird's talons and wings while the other stabbed at its heart. What had begun as rational, ended in hysteria; what began as mercy, ended in murder.

Audubon had to draw this huge raptor before rigor mortis set in, and he began immediately, "sweating by the fire or shivering as the embers died."

After five days of this labor he became sick and crazy with the effort; he took to his bed, tortured with guilt at what he had done. Parkman, who was managing the Boston subscription for Audubon's great volumes, felt doubly responsible as partner and doctor to the 'Woodsman of America.' Mrs. Parkman nursed him back to health with pots of tea, bowls of chowder and liberal small talk.

Whenever, now, I think about raptors, I think about that eagle "erect on its perch, its eyes glinting, body defiantly and resolutely alive" after America's most distinguished naturalist, and his Brahmin friend, had tried to suffocate it. I think especially about the glint in those eyes. Well before reading about this in Schama's book, however, I had experienced that glint in the eyes of the Gray Hawk.

"Raptor" and "Birds of prey" are terms for members of various families. Old World buzzards have traditionally been included, and I think New World vultures have been also -- though some authorities merge the New World vultures with the storks, and that would raise the question of whether storks are raptors. At any rate, the group includes the Hawk family, the Accipitridae, a family which has slightly over 200 species (and includes kites), the Falcon family, the Falconidae, a family with about 60 species, and the Owl families. The Hawk family includes eagles, which means that eagles are in fact large hawks, their size entitling them to a special name in the vernacular. It also includes buteos, of which the Gray Hawk is one.

Buteos are the soaring hawks. They ride thermal updrafts high into the sky and then circle about, resting on air. Their broad wings are perfect for this. They are of course looking for something to eat. The muscular body can instantly convert the soaring into a dive. Small birds, reptiles, small mammals are frequent prey.

Other hawks have other life styles. Accipters, of which the Cooper's Hawk is an example, prefer open woodlands, where they can scan the ground from the branch of a tree. Harriers glide relentlessly a few feet above marshy grassland (our Northern Harrier was previously named Marsh Hawk), tilting one way and then the other, scanning for rodents.

Among buteos, the Gray Hawk is especially prized by US birders. This is partly due to the fine gray coloration, but mainly to the fact that it can only be found in a few places in the US, all just over the Mexican border. The bird's total range is extensive: all the way south to Paraguay. (There seems to be something about northern Mexico that is exhausting to birds. Look at it this way: a surprising number of birds have enormous ranges which begin, in a sense, all the way down in South America, showing dominance and strength, as it were, but then sputter and peter out just as they finally near the US border. Northern Mexico does them in. A few push on a for a league or two more and are seen now and then, or even nest, on our side of this great divide).

I-10 between Tucson, AZ and Lordsburg, NM goes through a landscape which a scientist I know -- an ecologist charged with classifying the ecosystems of Arizona in technical terms -- described to me as "hot stinking desert." So much for technical terms. But this particular hot stinking desert is not just an ecosystem. It is also an important part of our history: this is the land of Cochise and Geronimo.

It is also the land of the roadside "attraction." The well-advertised roadside attraction. So well-advertised, in fact, that it is sometimes hard to see the desert for the billboards, most of them urging you to stop and see "The Thing."

"The Prehistoric Thing. A Mystery Through the Ages." What is The Thing? Do not read the rest of this paragraph if you want to discover this for yourself. A friend who stopped once to pay his admission says The Thing is a fossilized tortoise, a prehistoric relative of the desert tortoise. Another who also stopped says there is also an impressive collection of something else that is often found in situations like this -- no doubt you have already guessed -- black velvet art.

In March, I was on this stretch of I-10 in pursuit of the Gray Hawk. It was not stinking hot, but it was hot, and the journey started out in a most rewarding fashion, for as I was driving along I saw the Common Black Hawk, another south-of-the-border buteo that just makes it up into Arizona and a few other places in the Southwest. I stopped the car and was able to put my glasses on a lone bird flying below the horizon. This was the first time I had seen this species.

But the Gray Hawk is not found so easily. You have to know someone who knows where to find one. I was lucky, I knew someone. And he told me it is found at the Muleshoe Ranch, which The Nature Conservancy had recently acquired. I was thus not driving this stretch of I-10 just to see the Gray Hawk's darker cousin. I was on my way to the Muleshoe Ranch.

The ranch house was then a simple affair, notable only in being devoid of Southwestern charm. It looked more like a ranch house in suburban Chicago than one located in the center of a remote chunk of Arizona history. The house was set a little above a wide wash, dry now but impressive nonetheless. Down this wash, not far, was a nesting Gray Hawk -- or so they told me. (The house was next to a stand of black mesquite, a once extensive community type, now rare).

I checked the nesting tree as soon as I arrived on the 30th, and thereafter hourly until dark. No luck.

On the 31st, I decided to go for a hike. I walked up the wash, checking the nesting tree as I passed, walked for about an hour. It was hot and dusty. There were few birds. I found myself at the base of a steep hill on which Saguaro grew. I climbed up into the patch of Saguaro -- this improved the view but not the birding. I did not see Gray Hawks swooping majestically in front of me with prey dangling from their beaks on their way to feed the little ones.

On the climb down, the steep slope caused me to lose my footing at one point. My feet went out from under me, and I sat down on a pancake cactus -- Ouch!

The injury was as much to my pride as to my body. I made it down the hill and walked a little stiffly back to the ranch house, checking the nesting tree as I passed. But again, my vision was not disturbed by the sight of a gray raptor.

The house was empty. I was completely alone. The refuge manager and his wife had taken some friends out on an all-day trail ride to the far reaches of the ranch. I was in need of a hot bath. Fortunately, there was a small hot springs between the house and the wash. A pipe had been run into the hot springs so that it would trickle into a rectangular concrete trough just deep enough to make an inviting bath tub. There was nothing fancy about this arrangement, just an old concrete trough filled with some hot water alongside the wash of a dry river in the desert, in the shade of a few trees.

It seemed like heaven. I took off all of my clothes, all of them sweaty and dusty, and climbed in. I put my binoculars on the edge of the trough. I rested the back of my head on another edge and my feet on still another. The liquid heat began to sooth my perforated buttock. But the water was too hot to soak in comfortably for any length of time.

The water trickled out of the trough, however, between my feet and collected in a pool on the ground before making its way down to the wash. I thought that the water in the pool on the ground would be a little cooler, so I got up out of the trough and lay down in it. The bottom of the pool was mud, warm mud. I didn't mind this at all and settled down in the mud rather like a contented hog.

So there I was: in the middle of nowhere, all by myself, naked as the day I was born, a swine in slop. I looked up through a gap in the trees towards the wash. The Gray Hawk flew by, on its way to the nesting tree.

A man with true sang-froid would have just lain there and mentally placed a check in the appropriate box. I sprang straight up into the air rather like a cartoon character -- Wile. E. Coyote being surprised by the Roadrunner, beep-beep, perhaps. I was covered with mud. I somehow managed to achieve a certain rinsing-off of myself, put on some of my sweaty, dusty clothes (at least I remember putting on my shoes), grab my binoculars, and race down to the tree. I was rewarded with a great view of a Gray Hawk at the nest.

The field guides are very mundane in their descriptions of what is in fact a very handsome bird. "Gray upperparts, gray-barred underparts" says one. "Rather small and accipiter-like; relatively long-tailed" says another. Admittedly, light gray is not a color we birders typically get excited about, but in this case, I was struck by how it carries an air of formality that is unusual, the upperparts gray blending together in a way that suggests formal attire, rather like a cutaway coat. And the multitude of thin bars across the underside suggest a weskit. A pocket watch would be a nice addition. The Gray Hawk is like a man in a fashionable gray three-piece suit who comes to a meeting with others all dressed in blue suits. The Gray Hawk stands out.

With the help of the binoculars, I also saw the face up close and was able to study it. This was the first time I can remember being struck by glint in the eyes, the glint in the eyes of a bird of prey.

A list of the many topics brought up in this chapter can be found in Addendum.

See Photo Credits for who provided us with this magnificent image (full-size in full chapter).

Table of Contents

Home page ->For a listing of chapters that includes each bird's name, click on Random Footnotes.

All is journey, and in this case, 30 journeys. We can make these particular journeys riding webbook or ebook. The complete ebook, sans ads of course, is available now for

purchase: Click here.

The introductory web posting of the first two chapters is in full. Click Additional for other postings.

F.W. Benson

Birds treated, but not featured (see Photo Credits):